13 April 2006

Beckett fact no. 63.

Being born is never a good start, in Beckett. ‘Birth was the death of him’, begins A Piece of Monologue. ‘They give birth astride of a grave, the light gleams an instant, then it’s night once more’, Vladimir says in Waiting for Godot. ‘The end is in the beginning and yet you go on’, Hamm adds in Endgame. In Murphy, the newborn hero disgraces himself by putting a literal dampener on his arrival: his birth cry is not the ‘proper A of International Concert Pitch […] but the double flat of this [...] his rattle will make amends.’ The perfect mother, in the Beckett world, is quite possibly the one with no children, if that isn’t a contradiction in terms, which it is, but if children there must be, depend on the Beckettian male not to be very pleased about it. She could feel it ‘lepping already’, the pregnant Anna/Lulu taunts the narrator of First Love. ‘If it’s lepping […] it’s not mine’, comes the reply. In Watt, Tetty Nixon describes chewing through her own umbilical cord while her oblivious husband plays a game of slosh in the billiards room. No less keen to avoid the awful event, the father in the autobiographical text Company retires to his De Dion Bouton car during the birth of his son awaiting news that ‘it was over at last’. The end is in the beginning. Not that the child itself is any more pleased about all this. ‘A washout’, Henry remembers his father calling him in the radio play Embers: ‘wish to Christ she had’ he adds, of his mother. Molloy meanwhile credits his mother with having done ‘all she could not to have me, except of course the one thing, and if she never succeeded in getting me unstuck, it was that fate had earmarked me for less compassionate sewers.’

To begin in Beckett is to fail to begin, because the starting point is already too late; yet at the same time we’re always long since underway too, no matter what our reluctance, because the chance to stop has been missed. Throughout Beckett, there is a sense of simultaneous movement and stasis, hope and despair, fiasco and howling success, of circles that are both golden are vicious. The novel Molloy is a quest for the mother, a voyage that takes Molloy across mountains, planes and forests, in and out of captivity, with a murder along the way, before his final collapse in a ditch; and if we never reach our destination, maybe it’s for the good reason that we’re already there. The novel’s opening lines, after all, are ‘I am in my mother’s room. It’s I who live there now.’ Molloy is a book in two halves, and in the second we encounter a private detective, Jacques Moran, who sets out in search of Molloy. While failing to track him down, he duplicates aspects of Molloy’s narrative, down to the murder of a man in a forest, as well as degenerating physically, to the point where we start to wonder whether Moran hasn’t found Molloy by turning into him. But this time narrative circularity goes one step further. ‘It is midnight. The rain is beating on the windows’, Moran’s half of the book begins. He embarks on his journey, fails, returns to his home, finds it in ruins, and sits down to write his report for his shadowy boss, Youdi. ‘It is midnight. The rain is beating on the windows’, the report begins and the books ends. We achieve circularity: he writes the report that we have just read. Action and narration fold into one. Except his tale is not quite over. There are two more sentences: ‘It was not midnight. The rain was not beating on the windows.’ Action and narration split apart again: if the story is about to repeat itself, we can now supply a silent strikethrough or cancellation of everything we have read. The beginning is in the end, and this time we don’t go on. Even as Moran comes to rest physically, his narration is made to retrace its own steps, in confusion and denial. Vicious or golden, the circle cracks and fragments.

Given these games he plays with time, sequence and narration, Beckett licenses the reader to flit from one end of his work to the other, as I’ll be doing today, early to late, page to stage, poem to novel to radio play, because of our sense of it all as one work, one great echo chamber of his lifelong theme, from beginning to end. If at one point in Waiting for Godot we hear that ‘It’s never the same pus from one second to the next’, the next second we’re told ‘The essential doesn’t change.’ ‘The sun shone, having no alternative, on the nothing new’, runs the opening line of Murphy, with its much-noticed ambiguity. Is it the shining, or the shining on nothing new to which there’s no alternative? Or maybe both? There is nothing new under the sun, we think. And yet just a few lines later we learn that this sun is shining into Murphy’s north-facing mews, which most certainly is something not just new but impossible. The deadeningly familiar alternates with the unprecedented in Murphy: it’s never the same north-facing sun, with its nothing new, from one second to the next. And this is the key, I’d like to suggest, to Beckett’s work: progress not just in the face of, but precisely by means of the impossible.

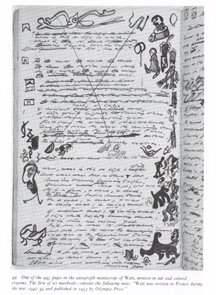

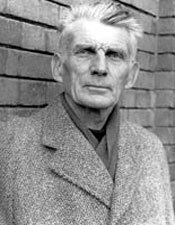

To circle back again to the end that was his beginning, Samuel Beckett was born in Foxrock on Good Friday 13 April 1906. In the addenda to the novel Watt, a peculiar ragbag of fragments stuck onto the end of the book, and which only ‘fatigue and disgust’ Beckett says prevented him from incorporating into the rest of the text, we encounter the peculiar little statement ‘never been properly born’. Of all his heroes, Watt is among the most passive and shadowy; if other Beckett characters are vocal about their grudge at being born, perhaps Watt isn’t because he thinks of it as a condition he has yet to experience. Instead he inhabits what another addendum to Watt calls ‘sempiternal penumbra’, ever-lasting half-shadow, the shelter of a beautiful phrase and a blissful exemption from the human condition the rest of us must endure. But Watt is about origins in one more ways than one, and not just foetal but Irish origins too.

To celebrate Beckett’s eightieth birthday in 1986, Eoin O’Brien published his illustrated study The Beckett Country about these Irish origins, and just coming here today from Bray I’ve passed through several of its districts. In Murphy, Neary considers going to ground in Bray, while between here and there is Redford cemetery, burial place of the writer’s parents William and May, and also of Belacqua in the short story ‘Draff’ and the inspiration for the cemetery in the later novella First Love too, ‘way out in the wilds of the country on the side of a hill, and too small, far too small, to go on with. Indeed it was almost full, a few more widows and they’d be turning them away.’ The Becketts kept a summerhouse in Greystones, where Samuel also played golf, and it was here (not Dun Laoghaire, as often claimed) that Beckett had the experience of ‘the vision at last’ we find, again, in Krapp’s Last Tape. Next stop down the coast is Kilcoole, which gives its name to an unpublished late play. A little further down is Jack’s Hole, where Belacqua and the Alba enjoy a not quite romantic tryst in Dream of Fair to Middling Women.

But to return to my ‘sempiternal penumbra’: for the most part the setting of Watt is non-specific but recognisably South Co. Dublin, down to the old Foxrock railway line that Watt appears to take to Mr Knott’s house, and with a reference or two thrown in to Leopardstown racecourse and Prince William’s Seat in Glencree. Throughout the novel Beckett indulges a series of jibes at the Irish Free State he had lately abandoned, its morbid religiosity, its philistinism and censoriousness. The country Watt inhabits is also one from which all trace of sexuality has been banished. Or as he says about the place in First Love: ‘What constitutes the charm of our country, apart of course from the scant population, and this without the help of the meanest contraceptive, is that all is derelict, with the sole exception of history’s ancient faeces.’ Ireland is identified with sterility and failure, a place in which it is impossible to be properly born. The young Beckett, as we know, itched to be gone, leaving for Paris in 1928 and moving there permanently in 1937, and after the war turning to French as his adoptive first language. And yet, as he also says in the addenda to Watt, ‘for all the good that frequent departures out of Ireland had done him, he might just as well have stayed there’. Because sterile though it may have been, Ireland continues to fester and breed for Beckett even after his embrace of French, repellent yet ripe soil for imaginative revisitings well into the 1980s.

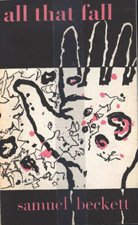

After the great outpouring of the trilogy of French novels, Molloy, Malone Dies and The Unnamable, with Waiting for Godot thrown in too for good measure, Beckett’s creativity slackened off a little in the 1950s, and when he received a commission from Radio 3, or the old Third Programme as it was known, he returned to both the English language and Ireland in the radio play All That Fall. Here again though it is failure and sterility that flower for Beckett. Once again the setting is his childhood Foxrock, now called Boghill. The elderly Mrs Rooney is making her way to the railway station to meet her husband Dan off the train. Terence Brown has noted that the Beckett universe is an oddly childless one, but in the Rooneys’ case there has been a child, a daughter, who has died. Decay is everywhere. A ditch full of rotten leaves might be the last from the previous winter or the first from the winter to come. Words too seem to have withered and died. ‘Do you know, Maddy’, Mr Rooney says to his wife, ‘sometimes one would think you were struggling with a dead language.’ ‘Well, you know’, she reassures him, ‘it will be dead in time, just like our own poor dear Gaelic, there is that to be said.’ During their walk back from the station, Maddy remembers attending a talk by ‘one of those new mind doctors’ on the condition of a young girl, as in that fragment from Watt, who ‘had never really been born’. She is drawing on Beckett’s own memories here of attending a talk at the Tavistock Clinic in London given by Carl Jung in 1935. The girl dies at the end of her anecdote, and she drifts off into a reverie on whether hinnies can procreate (they can’t, they’re sterile), but the comparison between the elderly but still grieving mother and the freedom from suffering of the dead young girl is stark. To live is to suffer, and as Sophocles preached, the best of all is not to be born.

For Mrs Rooney, her grief takes the form of occasional outbursts to other characters such as Mr Slocum and the comically low-church Protestant Miss Fitt, but where Mr Rooney is concerned something darker may be at work. As the couple walk home he hints at murderous passions: ‘Did you ever wish to kill a child? Nip some young doom in the bud.’ As the play ends the Jerry, the boy who normally guides Dan home, runs after the couple to return a rubber ball that Dan has dropped. When quizzed by Mrs Rooney about why her husband’s train was late, and to Mr Rooney’s evident annoyance and distress, the boy declares: ‘It was a little child Ma’am. It was a little child fell out of the carriage, Ma’am. On to the line, Ma’am. Under the wheels, Ma’am.’ Has Mr Rooney pushed him? It’s impossible to say. Had the child lived to old age, it too could one day enjoy the joke in the play’s title when Dan asks his wife what the text of the vicar’s sermon will be that Sunday. It is, in the beautiful prose of the King James Bible, ‘The Lord upholdeth all that fall and raiseth up all those that be bowed down.’ This is followed in the text by ‘Silence. They join in wild laughter.’

In dragging Beckett back to what I called the end that was his beginning, it’s important to acknowledge his Church of Ireland upbringing as not the least of many influences that shaped his worldview. Its imprint on his work was abiding: Krapp and the Unnamable sing Protestant hymns, Watt and Molloy ponder absurd but suspiciously well-informed theological conundrums, and Hamm in Endgame initiates a prayer whose blasphemousness was deemed unstageable in the 1950s. And given the hostage to fortune for the religiously-minded of the title Waiting for Godot, it’s tempting to suggest religion as one answer to the question of suffering I’ve been describing. Beckett was dismissive of the God inside Godot, however, declaring that had he meant God in the play he would have said so. Yet God is everywhere in his work, a point of imaginary guarantee to which his characters return for solace and reassurance even if, as they discover, there turns out to be nothing there. Irish philosopher Bishop Berkeley wondered whether a tree that fell over without anyone being there to hear it made a noise. Yes, is the answer, because God is there, in theory at least. In Watt, Mr Hackett reports an indecency on a public bench and, when the policeman finds none, protests he saw it ‘as God is my witness’; to which the policeman, obviously not a Berkeleyan, retorts, ‘God is a witness that cannot be sworn’.

Beckett’s characters look for cosmic reassurance and fail to find it, but instead of abandoning God at this point they only intensify their demands on him. The best example of this is Hamm’s prayer in Endgame. Trying and failing to pray, he curses God: ‘The bastard, he doesn’t exist!’ The logic of cursing something for its failure to exist is entirely Beckettian. As atheisms go, this couldn’t be further from the well-adjusted rationalism that Richard Dawkins preaches: Hamm’s relationship with his creator, one of anger and resentment, is based on the latter’s non-existence. If he thought He did exist Hamm could pray to him like anyone else, and where would the fun be in that? Another good reason for God’s non-existence would be that, if he was there, he’d have some explaining to do about the kind of suffering we’ve already seen in Beckett. The God invoked in Lucky’s great speech in Waiting for Godot gets his excuses in early: ‘Given the existence as uttered forth in the public works of Puncher and Wattmann of a personal God quaquaquaqua with white beard quaquaquaqua outside time without extension who from the heights of divine apathia divine athambia divine aphasia loves us dearly with some exceptions for reasons unknown’. Apathia: the absence of suffering. Athambia: the absence of feeling. Aphasia: the absence of speech. At his lofty remove he loves us dearly, but as Lucky dares to suggest, ‘with some exceptions’, though ‘for reasons unknown’. Religion is a closed system of absolute certainty, as vouched for by those public works of Puncher and Wattmann, and not required to explain itself to wretches such as Lucky. Yet by identifying with his misery instead of protesting at it, in his perverse way, by appearing to pass sentence on himself in the name of divine justice, Lucky allows something like the voice of this absent God to speak on stage. Could he do it if he wasn’t one of those unloved ‘exceptions’? If he wasn’t, then like Hamm he wouldn’t have any reason to unleash his torrential anti-prayer in the first place. As the German writer Walter Benjamin once said, Hope is given to us for the sake of the hopeless, and it’s thanks to his hopelessness that Lucky is able to articulate his tortured demand for hope in his comfortless world.

Earlier in that play, Vladimir and Estragon too consider the gap between religious theory and actuality, when Vladimir discusses the story of Christ and the two thieves. ‘Do you remember the story?’, he asks of Estragon, who doesn’t. But then just what the story is is far from certain, since as Vladimir points out only one out of four’ of the four evangelists tells the story of the good and bad thieves, while ‘Of the other three two don’t mention any thieves at all and the third says that both of them abused him.’ One solution to this discrepancy might be to consult the theological authorities quoted in Watt and Molloy; another is Estragon’s suggestion that ‘People are bloody ignorant apes.’ Another solution again, as with Lucky’s speech, is to identify with the hopelessness and confusion these unanswerable questions create, and to find the experience not just endurable but amusing too. As Winnie, buried up to her waist and later her neck in sand, declares in Happy Days: ‘How can one better magnify the Almighty than by sniggering with him at his little jokes, particularly the poorer ones?’

This introduces the theme of Beckett’s humour to the discussion. Before I go any further, I’m reminded of a short piece I saw once in the Guardian about the writer’s cat. Most people, the writer argued, like to believe in their pet’s intelligence, but what he found most endearing about his cat was its utter stupidity and inability to learn, ever, from its mistakes. Day after day the cat would sit by the door, despite the fact that he would get whacked every time someone opened it. Day after day the cat would whine to be let out, even when it was raining, then when he’d been let out in the rain would wait until the door closed before standing whining at it to be let back in. Just like that cat, what is so poignant about Beckett’s characters’ predicament is not how stupidly they behave, but how they never learn from their mistakes, no matter what the consequences. This discovery should be enough to see off that strange question, which even now gets asked about Beckett: isn’t it all very depressing? Isn’t he a terrible nihilist? – the answer being that, far from being nihilists, Beckett’s characters are the world’s worst nihilists, completely to give up, no matter how ridiculous their situation, dementedly insistent that they must go on.

Two famous passages on humour in Beckett bear out what I’ve been saying about failure and despair. In Endgame, Nell surfaces from her dustbin to announce that ‘Nothing is funnier than unhappiness’, while in Watt, the manservant Arsene gives us a whole theory of laughter and its connection to failure. There are three types of laughter, according to Arsene: the bitter, the hollow and the mirthless. The bitter laugh is the ethical laugh, it laughs at that which ‘is not good’. The hollow is the intellectual laugh, laughing at that which ‘is not true’, and the third and highest kind is the mirthless, so-called ‘dianoetic’ laugh, which laughs at that which ‘is not happy’. There is another name for finding people’s misfortunes funny, of course: sadism. I’m thinking here of Mel Brooks’s definition of tragedy and comedy: ‘tragedy is when I cut my finger. Comedy is when you walk into an open sewer and die.’ While there’s a fair deal of outright sadism in Beckett, as in the novel How It Is, with its fantastically detailed vision of torture, the humane point of this insight is the permission it gives Beckett’s characters to step outside their predicaments and find them merely absurd, rather than tragic. ‘Tears and laughter, they are so much Gaelic to me’ says Molloy, and throughout Beckett the one tends to blend into the other.

This has advantages but disadvantages too for the reader or theatre audience. The German critic Wolfgang Iser has brilliantly analysed what he terms the ‘interrupted laugh’ of the Beckett audience in the theatre. Consider again the case of Estragon and Vladimir in Waiting for Godot. They wait for Godot, he never comes, their situation is absurd, and we laugh at them. Then we remember how seriously they take it all: suppose they wait forever for this man who’ll never arrive? We feel guilty about finding their situation so funny and stifle the laugh in our throats. If we approach it the other way round, we might say: they wait for Godot, who will bring meaning to their empty lives, he refuses to come, it’s tragic; the play is an allegory for the meaningless of modern life. But then we see how the characters themselves respond to this situation, by treating it all as a bit of a joke, and we laugh at ourselves for finding it so tragic, and being so po-faced about it all. Whether we start with comedy or tragedy, we are shifted from our position by the play’s constant flip-flopping on how seriously it takes the Godot theme, and we are left somewhere in the centre that we can agree to call ‘tragi-comedy’. We are pushed into this position by the play’s refusing to be one thing or the other: it sets up its contradictions and simply refuses to give us anything resembling a traditional resolution. Vivian Mercier was the critic who described Godot as a play in which nothing happens ‘twice’, in the play’s two acts that is, but what he had identified was Beckett’s ability to take the play’s themes of inaction and absence of resolution, and rather than compensate for or work around them, to turn them into the basis of its success. Estragon and Vladimir laugh at themselves, we laugh at them, we laugh at ourselves, the play refuses to give us anything we might normally expect from a play and we laugh at that too.

Godot is a womanless play, and women, it must be said, tend to feature as inaccessible love objects, prostitutes and hideous grotesques in the early Beckett before the marvellous female characters of the second half of his career, roughly from Mrs Rooney onwards. I mention women here to introduce another key theme that Beckett runs into the ground in search of an exit that never comes from failure and unhappiness: love. ‘I associate, rightly or wrongly, my marriage with the death of my father, in time’, begins the novella First Love. This too is a text with an Irish origin, dealing as it transparently does with the long depressive concussion that followed the death of Beckett’s father in 1933. The narrator is first abandoned by his father, who dies, and then by his family, who expel him from the family home. In his morbid nostalgia for the dead father, the narrator indulges a much-quoted passion for cemeteries:

Personally I have no bone to pick with graveyards […] The smell of corpses, distinctly perceptible under those of grass and humus mingled, I do not find unpleasant, a trifle on the sweet side perhaps, a trifle heady, but how infinitely preferable to what the living emit, their feet, teeth, armpits, arses, sticky foreskins and frustrated ovules. And when my father’s remains join in, however modestly, I can almost shed a tear. The living wash in vain, in vain they perfume themselves, they stink.

In his grief-induced psychosis, the narrator has problems telling the simplest things apart. For instance, he is a prey to terrible constipation, and it is during one such episode that his family empties his room of his things. Yet, describing it, he wonders: ‘Or am I confusing it with diarrhoea?’ Constipation might be mistaken for many things, but not, one would have thought, diarrhoea. Similarly, the two very different concepts of love and death appear to become fatally confused in his mind. Sitting on a canal bank bench (perhaps the Grand canal bank benches so beloved of Patrick Kavanagh), he is accosted by a prostitute. His first instinct is to rebuff her violently. His interest in his fellow humans, after all, appears limited at best: ‘I didn’t understand women at that period. I still don’t for that matter. Nor men either. Nor animals either.’ When he decides, suddenly, inexplicably, to succumb to her, he announces his love by tracing her name in a cowpat. In his desire to emulate the father he must pass through the ordeal of love, but since the father is dead, he can only do so in a morbid, excremental way. Soon enough, he impregnates his prostitute girlfriend. This leads to the ‘If it’s lepping, it’s not mine’ exchange I quoted earlier, at which point the narrator walks out to the diminishing sound of the child’s cries in the background: ‘as soon as I halted I heard them again, a little fainter each time, admittedly, but what does it matter, faint or loud, cry is cry, all that matters is that it should cease.’ I’ve been reading this text for many years, but only recently did it occur to me to wonder why the narrator doesn’t dispute the child’s paternity. For such a feckless man, and given his lady friend’s profession, this would seem the obvious escape clause. On a deeper level though, I would suggest that the narrator desires and needs the child to be his, in order to walk out on it. He is doing unto his child as his father did unto him: abandoning it. ‘What goes by the name of love is banishment’, as he says, and without any conscious cruelty, perhaps even thinking he is doing the child a favour, he passes on the priceless Beckettian gift of abandonment and solitude. Rather than hauling him back from his necrophiliac madness, the narrator’s taste of love only exaggerates it, and perpetuates the miserable cycle through another generation: ‘but there it is, either you love or you don’t.’

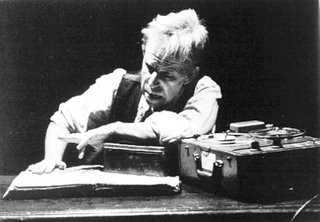

Someone else who has loved in Beckett is Krapp, of last tape fame, who pores obsessively over his recorded memories of a romantic afternoon with a woman in a punt: ‘We lay there without moving. But under us all moved, and moved us, gently, up and down, and from side to side.’ This is Krapp’s lost love, and the play exists in the wistful space between the disillusioned present and the once-happy past. Or it would do if it wasn’t for Beckett’s brilliant twist of the knife: Krapp sits on stage listening to his past self on tape, and for the younger self on tape this scene in the boat is already long past and gone. The vista into his past is not just a hall of mirrors, but a hall of distorting mirrors. Krapp is an interrupted being, Beckett said of him. He listens to snatches of sentences on the tape, stops, rewinds, fast-forwards. The narrative of his life is a series of fragments that no longer add up to a whole, if they ever did. When he finally gets round to recording this year’s birthday tape, on-stage Krapp confesses that his love interest is now the slightly less glamorous figure of ‘Fanny’, that ‘bony old ghost of a whore’. ‘How do you manage it, she said, at your age? I told her I’d been saving up for her all my life.’ In his early study of Marcel Proust, Beckett discusses the changeable nature of human identity through time, and in Krapp’s case, the man on stage knows he was once this other, unillusioned young man, but cannot feel or understand how he could still be the same man. As he says himself, ‘Just been listening to that stupid bastard I took myself for thirty years ago’. But the afternoon in the boat is burned too painfully on his memory to erase entirely, and the play ends with him listening to the taped description of it one last time. The tape comes to an end, and rather than turn it off Krapp sits in silence staring forward to the accompaniment of its wordless whirring. What I see happening here is Krapp at rock bottom, completely disconnected from any chance of happiness and disconnected from his own life too. But having realized his failure, I would argue that he achieves a moment of togetherness and union with his younger self at last in the doubled-up silence I’ve just described, of on-stage and recorded Krapp, both sitting in silence. He achieves this breakthrough, but only by means of first realizing and embracing his complete human failure, and the utter lostness of the love he describes.

‘Words have been my only loves, not many’, the narrator of First Love says, but if everything else in Beckett’s world falls to bits and lets him down, it would be far too easy to say that at least language is always there to cheer him up. Language too falls to bits as much as anything else. Consider, for instance, the back-to-front, or as Beckett might say ‘arsy-versy’ evolution of his writing over the decades, whereby in the 1930s he can do plots, characters, real-life settings, only for these things to fall away one by one, until in his very late texts he can barely string a sentence together anymore. In How It Is, written in a series of gasping fragments, he speaks of ‘little blurts midget grammar’, and by the time we reach Worstward Ho in 1984 the grammar may strike readers as not just midget- but amoeba-sized. A major theme of the 1940s trilogy was the search for the true self, and the battle to take possession of the first-person pronoun ‘I’, but by the time we reach Worstward Ho all traces of pronouns and who, exactly, may be speaking the text have vanished. Here are the opening lines of the text:

On. Say on. Be said on. Somehow on. Till nohow on. Said nohow on.

Say for be said. Missaid. From now say for be missaid.

Say a body. Where none. No mind. Where none. That at least. A place. Where none. For the body. To be in. Move in. Out of. Back into. No. No out. No back. Only in. Stay in. On in. Still.

All of old. Nothing else ever. Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.

We start where The Unnamable broke off, going ‘on’. But something isn’t right, as the voice has to reassure itself: ‘Say on’. Then it doubles it up in the passive voice too: ‘Be said on’. We sense some kind of obstacle here, as the text exhorts us ‘Somehow on’ before admitting defeat: ‘Nohow on. ‘Said nohow on.’ In Beckett’s earlier fiction, the sense of blockage might lead to a torrent of resistance, such as the Unnamable spews forth. But something has changed. The title of the prose work before Worstward Ho is Ill Seen Ill Said, and in these late works Beckett explores the possibility that all seeing is ill-seeing, all saying missaying, and rather than protesting any more about it, decides to see where such a discovery might lead. Hence it is that he can ‘say a body. Where none’, setting it up and knocking it down in almost the same gesture, in a shadowplay of flickering presence and absence. It also makes it increasingly difficult to tell success from failure, on the text’s own terms. As Beckett writes: ‘Try again. Fail again. Fail better.’ No sooner has Beckett discovered a vocabulary for absolute cessation, inactivity and failure, than he undercuts it again in search of a further ‘meremost minimum, that makes the previous effort, in retrospect, look positively ‘lepping’ with activity. Listen to how Beckett reduces the better/worse pairing to a mischievous pair of identical twins: ‘Fail again. Better again. Or better worse. Fail worse again. Still worse again.’ What counts as better here, and what as worse? Is Beckett saying it’s better to be worse than better? Or aiming for a better quality of worseness? In which case, shouldn’t he be saying ‘worse worse’, not ‘better worse’? The fact that he grouped these three 1980s texts, Company, Ill Seen Ill Said and Worstward Ho, together until the title Nohow On means it isn’t just me who detects the ghosts of Tweedledum and Tweedledee here, distinguishable only by their lapel mottoes, ‘Nohow On’ and ‘Contrariwise’.

There is a newfound serenity in these late works, but if they seem not just resigned to fail, but to fail to fail, as Worstward Ho might put it, I’m not about to suggest that Beckett is belatedly smuggling in a form of happy ending. Not the least impressive thing about these late works is their ability to lay on just enough serenity before hitting us with a sucker punch in the stomach to remind us that 1980s Beckett is no more mellow or reconciled than he had been fifty years ago. For instance, Company returns to the theme of religion by wondering if the voice it hears in the dark mightn’t have something to do with God, ultimate provider of ‘company’ in the otherwise godforsaken dark. ‘God is love. Yes or no? No.’ Ill Seen Ill Said too locks onto its vision of extinction without an atom of remorse, longing to be rid of ‘Sky earth the whole kit and boodle. Not another crumb of carrion left. Lick chops and basta. No. One moment more. One last. Grace to breathe that void. Know happiness’, where even the pun on ‘Know’ with a k undercuts the pleasure the text takes in its own disappearance. To know happiness may be to enter a state in which there will be no happiness, and nothing much else either. The text acts as its own anti-midwife, giving birth to itself into death, turning the screws on its own thumbs, until it reaches a condition, in the words of Worstward Ho, of ‘Best worse no farther. Nohow less. Nohow worse. Nohow naught. Nohow on. Said nohow on.’

In the short French novel Mercier and Camier, the two heroes makes a series of abortive attempts to leave a city not without resemblances to Dublin, but constantly slouch back to their point of departure. So it is too with the themes I’ve looked at today: birth, childhood, Ireland, God, love, language itself. All seem to go dead for Beckett and drive him off in disgust and despair, yet over and over again he doubles back on them, unable to leave them alone; and the more sterile and worked out they become the more irresistible the allure of return. In his little book of Proust, Beckett characterised the artistic endeavour as excavatory, while also alluding to the ‘ideal core of the onion’, or empty core that may await us when our excavations are complete. If his own life’s work is a prolonged act of excavation, Beckett hits paydirt at last when he swings the icepick of language and nothing remains to connect with. This, I’d like to argue in closing, is what happens in his great, last artistic statement, the poem ‘what is the word’. ‘What is the word’ is both question and answer: as the poem flails about in search of the lost word that will make sense of all this confusion, it dawns on us that ‘what’ itself may be the word, and the question its own answer. Beckett circles – circles again – back to this refrain throughout the poem, with all manner of diversions, dead ends and interruptions, before finally repeating the refrain across a stanza break, the first time with a dash at the end, the second time without:

what –

what is the word –

seeing all this –

all this this –

all this this here –

folly for to see what –

glimpse –

seem to glimpse –

need to seem to glimpse –

afaint afar away over there what –

folly for to need to seem to glimpse afaint afar away over there what –

what –

what is the word –

what is the word

That settles it then: the question answers itself and the circle is complete. Except it doesn’t because the answer is merely another question and the circle cracks open as surely as the end of Moran’s report does in Molloy. In the first act of the play Happy Days, Winnie is buried up to her waist, and in the second up to her neck; in the implied third act, she is buried over her head and, who knows, perhaps still jabbering away under the sand. ‘What is the word’ doesn’t come to an end either: it merely breaks off. If there is an answer beyond that ‘what’, it lies in the silence of the unwritten next line. The poem ends where it begins, allowing us to circle back on this cracked circle and begin all over again. In the end is the beginning and in the beginning is the end, and yet we go on. Except that in the spirit of the Unnamable, who finally resolves to ‘go on’ and promptly breaks off, I’ve now reached the end of the beginning of my end, and in final homage to the Beckettian version of broken-down, better-worse, going on will, with many thanks, to him and to you, break off.

4 comments:

Beckett query no. 4: You mention Krapp singing a Protestant hymn (Eudoxia). The hymn is missing from John Hurt's version in the Beckett on Film series: is there any authority for that in the notebooks, or is it simply a decision of the director, Atom Egoyan's?

The hymn is Sabine Baring-Gould's 'Now the Day is Over', and was dropped by Beckett from productions he directed. ‘He might sing something, but not that’, as he told James Knowlson.

Still, it's there in the faber text, and I'm rather fond of it. A pity.

Do you happen to have any clues that can help me ge4t to the meaning of Sedendo et Quiescendo?

Thanks'

Post a Comment