Roy Fisher: always liked him a lot. Rereading him recently reminded me of this piece about

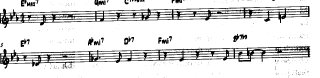

The Cut Pages in

Poetry Ireland Review a while back.

As gestures go, publishing a

Collected Poems before you turn forty would seem to be on the grandiose side, but when Roy Fisher (b. 1930) published his in 1969 he hadn’t been writing for several years and wasn’t expecting to again. What readers might have thought was a smirk on his face was in reality closer to a valedictory grimace.

Collected Poems came with a jacket photograph of a young boy at a street party in Birmingham for George V’s silver jubilee. The scene is straight from a poem like ‘Toyland’, with its ‘old couples, the widowed, the staunch smilers, /The deprived and the few nubile young lily-ladies.’ The youngster doesn’t look very impressed with his plate of biscuits either, and unlike most of the other revellers hasn’t bothered to put his paper hat on. A sharp-eyed observer might diagnose a case of proleptic post-imperial ennui, as the crowd waits for the barbarians at the gate who, even in 1935, must have been looking like ‘a kind of solution’, as Cavafy would put it. Fisher’s classmates, after all, express a ‘half-shocked envy’ when his aunt and two cousins are blown up in a bombing raid a few years later. As for Fisher himself, he has never been one for nostalgia: ‘I had no pain of it; can find no scar even now’. Philip Larkin does a good job of blanking out wartime Coventry in ‘I Remember, I Remember’, but not before he had permitted himself the wistfulness of ‘The March Past’ and its ‘astonishing remorse for things now ended /That of themselves were also rich and splendid /(But unsupported broke, and were not mended)’. Fisher’s unastonished blankness in the face of the national question, by contrast, is consistently unflinching. In ‘The Nation’ he describes a ‘national day’ on which everything described is prefaced by the adjective ‘national’, reducing the concept to a state of pleonastic exhaustion long before a group of offenders are clapped in the ‘national prison’ and subjected to the ‘national /method of execution’ for succumbing to the ‘national vice’, whatever that might be.

Organising a nationwide party to mark the occasion might be a bit excessive, but readers sitting down to Fisher’s work for the first time would have every right to feel in celebratory mood. Why wouldn’t they? He’s one of the best English writers around. Yet for all the superlatives I may wish to throw in his direction, Fisher’s position in British poetry today is an uneasy one. A lot of his books are hard to find or long out of print. Sometimes his anthology number comes up, but sometimes it doesn’t. Like Philip Larkin he loves Pee-Wee Russell and Coleman Hawkins, but unlike Larkin he also likes the Black Mountain Poets and has been known to call himself ‘a 1905 Russian Modernist’, which suggests that membership of the ‘old-type natural fouled-up guys’ club will forever elude him. Though held in great esteem by admirers – as witness the

Festschrift,

News for the Ear and John Kerrigan and Peter Robinson’s essay collection

The Thing About Roy Fisher – he has never quite loomed large enough in the landscape for the readership he needs and deserves. There was a Fisher Collected in 1969 but there wasn't as recently as 2004, before the appearance of

The Long and the Short of It: Poems 1955-2005, and if that isn’t a textbook definition of the phrase ‘arsy-versy’ I don’t know what is.

Fisher’s first book,

City, appeared in 1961. Robert Conquest’s Movement anthology,

New Lines, was still policing sphincters up and down the land, but foreign help was at hand the following year in the form of Alvarez’s

The New Poetry. The names on the team sheet were Lowell, Berryman, Plath and Sexton. If only things had been that simple! The delicious irony of The New Poetry was that, for an anthology so concerned to blast British poetry out of its ‘gentility principle’, Alvarez fell prey to an American gentility principle of his own, suppressing any suggestion that the American poetry of the 60s might also stretch to Ginsberg, Duncan, O’Hara, Schuyler, Rakosi, Oppen, Dorn, Niedecker or Spicer. Any writers under their influence on this side of the water were thus doubly excluded. A crucial conduit of alternative American writing in Britain was Fulcrum Press, publisher of Fisher’s study in itchy paranoia

The Ship’s Orchestra, Collected Poems and

Matrix, and most unusually of all the book I want to discuss here,

The Cut Pages. Sketched as an attempt to shake off a long spell of writer’s block, this is still the most extreme of his books and to some critics (notably Marjorie Perloff) his truest and best. Discontinuity is all, freedom from what Beckett called ‘the vulgarity of a plausible concatenation’. As Fisher puts it in an author’s note, the aim was ‘to give the words as much relief as possible from serving in planned situations; so the work was taken forward with no programme beyond the principle that it should not know where its next meal was coming from.’

Before turning to

The Cut Pages I would like to propose the phrase ‘Tennis Court Oath syndrome’ as a contribution to literary discourse. Tennis Court Oath syndrome is what happens when readers think they’ve worked out something startling and new, only for the writer to turn around and trump them with something not just startlingly new but incomprehensibly so, even and precisely at the risk of alienating his or her greatest admirers. Since I’m naming it after his notorious second book, John Ashbery displays Tennis Court Oath syndrome, or did once, a very long time ago. But sooner or later all writers have to decide where they stand on the innovation question. Some make it the driving force of their careers, turning from the ‘plane of the feasible’ in disgust, as Beckett urged Duthuit, ‘weary of pretending to be able, of being able, of doing a little better the same old thing, of going a little further along a dreary road’; others would have us believe that ‘All we can do is write on the old themes in the old styles, but try to do a little better than those who went before us’, as Hardy told Robert Graves. To describe

The Cut Pages as a case of Tennis Court Oath syndrome, coming as it does after the not exactly easy reading of

The Ship’s Orchestra, is to underline just how extreme a departure it was. But Fisher has never innovated for innovation’s sake or because he expects a congratulatory telegram from the academy of fine ideas: the dust jacket of

The Cut Pages warns that ‘he should not be categorised as an “experimental prose writer”’, and ‘does not fit any of the familiar formulae of modernism.’ If they were familiar, they’d hardly be any use anyway. The motivating force behind

The Cut Pages was more urgently personal and painful than that.

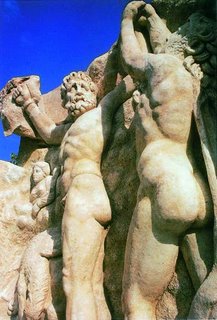

To start with the title: the pages are ‘cut’ because, keeping a ‘diary of demoralisation’ after a divorce and during his writer’s block, Fisher tired of having to skim past the old entries, so he tore out the blank pages and started again. Even so, the diary-like ‘entries in their hundreds’ that followed this fresh start were ‘oblique, coded, desperate and dispiriting.’ The resulting book is 80 pages long, and divided into five sections: ‘Metamorphoses’, ‘The Cut Pages’, ‘Stopped Frames and Set-Pieces’, ‘Hallucinations’ and ‘The Flight Orator’. The opening note describes the ‘Metamorphoses’ as ‘exercises in changing, in full view, one thing into another whose nature was quite unforeseen at the outset’. Where elsewhere in the book Fisher pares his language down to miniature stumps and shells of sentences, here he delivers a hypnotic superabundance of detail that makes the language swim before the reader’s eyes. In the first metamorphosis he describes a sleeping woman who changes into a swimmer, perhaps the swimmer we find in the first of the ‘Stopped Frames and Set-Pieces’ (and on the uncredited cover painting). The language sins against the Low Church modernist style-sheet in its unabashed embrace of metaphor:

Enough depth. To clear and come free. There is no taste in the water, there are no edges under it: falling away, the soft mumbled hollows and mounds of marble, veined with brown, a lobby floor gone down into the descending levels of a sea-basin. The sleep comes naked

Rising through the clear fluid, making their own way, the dragging wisps of brown that were secret hairs or the frame of a print on the wall. And light that cracks into the bubbles near the surface, lighting them like varnish bubbles, breaking them into the silent space between the surface and the curved roof, threaded with moving reflections of water light.

In the absence of any controlling narrative voice, the metaphoric transformations threaten to overwhelm rather than reassure the reader, building into a ‘mass of things, indistinguishable one from another’. Information throws itself at the text faster than Fisher can process it: a man is ‘making for the ferry; no he’s not. He stands a while and goes somewhere else.’ For all their morphing minute particulars, one thing the metamorphoses refuse to mutate into is a worldview: ‘No system describes the world’. But this is not to license a return to self-sufficient empiricism. As Fisher observed of William Carlos Williams’s famous dictum, ‘The trouble with “No ideas but in things” is that it has become an idea.’ Unlike Williams, whose red wheelbarrow means just that, a red wheelbarrow, Fisher gives the impression of unmooring his objects to wander as they please. They are ‘dying to get out’ and ‘exposed to the open at all events’. The chain of metaphoric substitution in the visual field responds to and shapes an urban environment in constant destructive evolution: ‘Washes of screen. Men are fluttered. Houses are being thrown away wholesale. Butchers are on air.’

The description of a man undressing in the fifth and final metamorphosis prepares us nicely for the stripping away of the narrative exoskeleton in the book’s titular central section. One sure way to misrepresent ‘The Cut Pages’ would be to quote it within a prose paragraph like this, rather than on its own visual terms: if its atomised elements mean anything, it is in conjunction with the white space that separates them, much like the pauses for breath between ‘versets’ in Beckett’s

How It Is. Each fragment establishes and is as suddenly forced to relinquish its hard-won textual space. What drives the text onwards so relentlessly, snatching the ground from under its feet? Fisher isn’t saying. ‘There is no process’ but ‘There are many changes’. Attempting to make sense of this densely resistant writing Perloff has suggested that the sequence is organised around ‘three sets of verbal clusters: (1) references to ordering, control, containment; (2) references to movement, change, opening, journeying; and (3) images of vision and items that obscure vision – shade, shadow, shutter.’ In support of this we can point to Fisher’s reliance on (dis)orienting terms such as ‘frame’, ‘frameless’, ‘cut’, ‘origin’, ‘displaced’, ‘discontinuity’, ‘undifferentiated’ and ‘process’, as the text ceaselessly changes perspective, attempting to bring into focus the experience of flux itself. When Donald Davie made his strenuous effort in

Thomas Hardy and British Poetry to align Fisher with Larkin as a poet of rooted nostalgia for post-industrial Britain, he was forced to turn a blind eye to the jump cuts and discontinuities in Fisher’s work; but, to do him justice, even in the forbidding atmosphere of

The Cut Pages the language of rootedness and community mysteriously persists:

Leviathan Lane. Home of the Works. Appears to have rolled over and huge stretches of its ghastly grey underparts come into view

Stern of a spiral stair depending through glass light, in going down, in confined but neatly stacked office and reception space

There is one flung out. On that one the light is sharp. There is no half-light; only the grace of diffusing what is full

They try to get in through the frosted glass, their spidery dark hands show almost visible as themselves as they scrabble. They come only at one oblique off-centre place; they can’t succeed

Accretions after origin. Atypical hazard. All we are worrying about is our own distress at their frustration

Communitas. On the march. March a path to march on

I owned a patch, they marched on it. What march is that? My tit

Here is the ‘dispirited avoidance of concept, copula, cognition’ which Simon Jarvis has found in Fisher at his most extreme, but as Fisher insists ‘This discontinuity is my discontinuity’, not just any old statement of an abstract predicament. The obsession with lighting effects stages a series of theatrical spaces from which any actors have gone maddeningly absent (‘Nobody has to have a face. Nobody who has a face can keep it.’) The ‘they’ are the off-stage prompters, town planners and literary aldermen laying down the city boundaries to which our urban and poetic narratives are expected to adhere. Fisher’s repeated acts of cutting into his urban and narrative space allows him to find a fissure (the Fisher fissure) in these continuities and lose himself down it, White Rabbit-style. Or as he says in section three, ‘so much isn’t the railroad, so little is.’ Another useful insight from Perloff is her comparison of the fourteen sections of this central sequence to the fourteen lines of a sonnet. The complaint that this writing is formless and sprawling has no foundation whatever; it’s just that, as with the mystical urban geometry of

A Furnace, the patterns are taking place over lengths beyond the visible limits of the two pages open before us. Stand on the Cerne Abbas man and you may notice that the earth beneath your feet is all chalky white, and nothing more; if you want to see the Cerne Abbas man you’ll have to go and stand on the hill opposite instead. Trying to get the patterns of The Cut Pages into focus demands much the same effort.

The 1987 reprint of

The Cut Pages contains only the central sequence, which leaves its relation to the original other four sections in some doubt. My preference is to see them as analogous to the ‘Addenda’ to Beckett’s

Watt, whose ‘precious and illuminating material should be carefully studied. Only fatigue and disgust prevented its incorporation.’ Particularly attractive is the description from ‘Hallucinations’ of the tombstone maker’s yard and the discarded trunks of statues littering it. Here we confront not just a graveyard of possibilities, but a graveyard’s graveyard. The albino raven Fisher finds there is emblematic of aborted promise, reminding the poet how ‘There are suburbs I have never properly visited, or have never managed to find recognisable as I passed through them, districts that melt into one another without climax.’ In the same way that Bishop Berkeley’s God has to be in the forest when nobody else is, to hear the tree falling, the raven allows Fisher to assert an imaginative claim to parts of his city he hasn’t ever bothered to visit. Unlike Yeats’s fantastic bird singing for the lords and ladies of Byzantium, the albino raven is the work of puffy-eyed and crablike artisans who supply pet-shops or garden centres. Amid such multiple resignations of the Romantic inheritance does Fisher reign over the peculiar domain of

The Cut Pages, with a mixture of implacability and bewilderment: ‘Slowly this bird and I are working on each other. The only rule in our game is that neither of us must appear to change.’ ‘So hoarily embedded in symbolism’ in appearance, it can only be bad manners on the bird’s part not to croak an obliging ‘Nevermore’ from time to time. But no, it won’t. As Fisher writes of another bird, the ‘great fat thrush’ of the book’s last section, ‘The Flight Orator’, ‘He may be dead; he may be struggling under the ground for a long while. Nothing can reach him. Nothing of this will ever be repeated.’ Any further inquiries can to referred to the final Watt addendum: ‘no symbols where none intended’. And yet the effect of all this atomisation and flux is not to silence Fisher’s work; its singular achievement is, patiently, ingeniously, to make these very things speak. As he writes at the end of ‘Toyland’ of his T.F. Powys-like townsfolk going about their business:

The secret laugh of the world picks them up and shakes them like peas

boiling;

They behave as if nothing happened; maybe they no longer notice.

I notice. I laugh with the laugh, cultivate it, make much of it,

But still I don’t know what the joke is, to tell them.

Fisher’s poetry picks its readers up and gives them a good shake, but only the most obtuse could behave as if nothing were happening. Most will have the good sense to acknowledge how they have been marked with a permanent but indefinable response, at once subtle and momentous, a mixture of a smirk and a grimace at the secret laugh of the world.